Photo Modes

“For starters let’s try to take a decent photo, […] with the sunset in the background.” An innocent, surely unsuspicious sentence we might overhear from a group of tourists with cameras hanging from their neck, standing in front of a postcard-like sunset. Sunset pictures themselves may even be considered the quintessential photographic subject, invading our screens and flooding the world’s servers. One might say it doesn’t get more photographic than this. Yet this sunset is somehow different. The voice we heard belongs in fact to YouTube user Franzo Games and the sun he is trying to frame and capture can be found within the video game environment of Next Car Game Total Wreckfest. Franzo Games stops the car racing game and activates the Photo Mode from the main menu. Photo Modes are a new function that appeared in big-production video games rather recently, a strange feature that is also associated with an equally bizarre-sounding phenomenon called in-game photography.

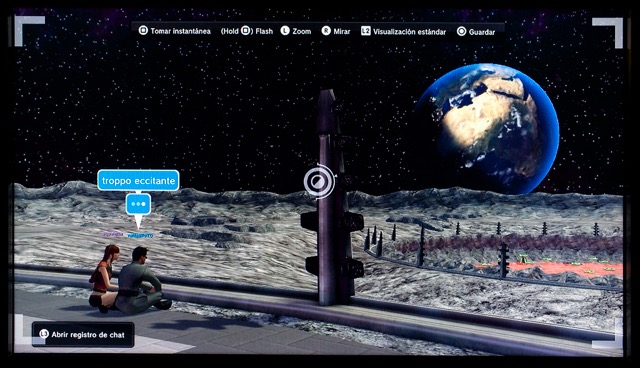

As explained by Naughty Dog’s official tutorial video on Photo Mode, this feature “allows you to freeze action in the game, adjust the camera and add custom effects and frames before sharing them”. Photo Mode can be activated at any time during gameplay by simply pushing a button on the game controller. This stops the game and brings up an interface to customize one’s picture, before being able to save it and share it. These customizations simulate functions of traditional analog photography, like the field of view and zoom functions, the depth of field and focus options, brightness and film grain (this perhaps a simplified version of the ISO concept in film photography), or the ability to frame the shot freely moving the virtual camera around the scene. After setting up the image in frozen gameplay, Photo Mode also allows users to add a variety of color filters, vignettes and frames. These features set the Photo Mode apart from the simple act of “screenshotting” or “printscreening”, directly referencing some aspects of the camera apparatus and notions of traditional photography. Zooming, focusing, and changing aperture to modify the depth of field all are very familiar techniques borrowed from the world of analog cameras. Suspended in the frozen moment, the scene leaves the game-photographer free to move in 360°, extending an instant for as long as she pleases before she is satisfied with the composition and ready to finally take the picture. It feels like an augmented, exploded, virtual photographic moment. So what exactly are these Photo Modes, where do they come from and what can they ultimately tell us about photography itself?

This new photographic addition and its fast spreading in-game images became so popular to the point that Time magazine commissioned war photographer Ashley Gilbertson to document the game’s protagonists through the Photo Mode and compare his experience on the field with its game equivalent. This ambiguity between traditional photographic notions and in-game picture taking lies in the faithful simulation of the camera functions, but also in an increasing visual similarity between game images and photographs of the physical world, due to the ever-growing photorealism in mainstream video games and the photographic looks of computer generated images in general. Often we are presented with images where we are in doubt about the source, or where we simply cannot believe that we are not looking at a “real picture”. This allows Franzo Games to say things like “let’s try to take a decent photo, […] with the sunset in the background”. Thanks to the likeness of the camera functions as well as the game environment's realism, the user is able to operate a direct and seemingly transparent association with photography.

Photo Modes simulate photography through photorealism and this also allows them to retain photographic qualities of indexicality: they act as documents of something that happened and as personal or collective memories for players. If we go back once more to Franzo Games’ YouTube introduction of the Photo Mode of Next Car Game Wreckfest we find him trying to take “a picture during a collision”. This sentence can sound a little strange (and worrying) if heard from a photographer outside of a computer game, but the attempt to capture a specific event in time is reminiscent of the idea of decisive moment of Cartier-Bresson and the whole genre of street photography. This idea of indexicality however is not specific to Photo Modes, but already present in the more “basic” and immediate remediation of photography in digital spaces that is the screenshot.

Photo Modes are a complex and hybrid phenomenon that remediates photography as well as screenshot practices in video game spaces. They retain certain qualities that can be identified as photographic while being completely independent from light impression mechanics that lie at the basis of how a camera operates. Photographic realism of game design allows to retain aesthetics and semiotics from photography and other visual media, while incorporating new aspects of sharing connected with specific potential of the distributed image and the online network. In-game photography is itself a much wider ranging and diverse phenomenon not isolated to the world of Photo Modes, but including screenshots, photography simulation games and photographic game user-modifications. Spreading globally around communities of practitioners ranging from amateurs to artists, they populate countless online forums and social media platforms. All of these remediations, mutations, virtualization of photography in game spaces make for an exciting and ambitious redefinition of what photography is becoming. Finally this all leaves us wondering what the act of taking photographs really means when the camera disappears, when the moment is frozen before we even take the shot and when the sunset we are framing is already made of pixels before we press the shutter.

Marco de Mutiis is an artist and curator with a focus on language, perception and communication. As a curator his research lies in the exploration of new forms of photographic practices beyond the camera, mutations and remediations of photography, and new approaches to the way images are created and distributed. Currently he is working as digital curator for Fotomuseum Winterthur and research associate at the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts (Switzerland).